Every year in Japan, as the rainy season (tsuyu 梅雨) begins, a quiet ritual takes place in many households: umeshigoto, or “plum work.” This refers to the seasonal practice of preserving ume (Japanese plums), a tradition that turns fresh, tart fruit into delicious pantry staples like umeboshi (pickled plums) and ume-syrup (plum syrup).

This year, I finally decided to give it a try myself.

I’ve always thought of umeshigoto as old-fashioned, and only grandmas would do. But now, I love it!!

🍃 Step 1: Bringing Home Fresh Ao-ume

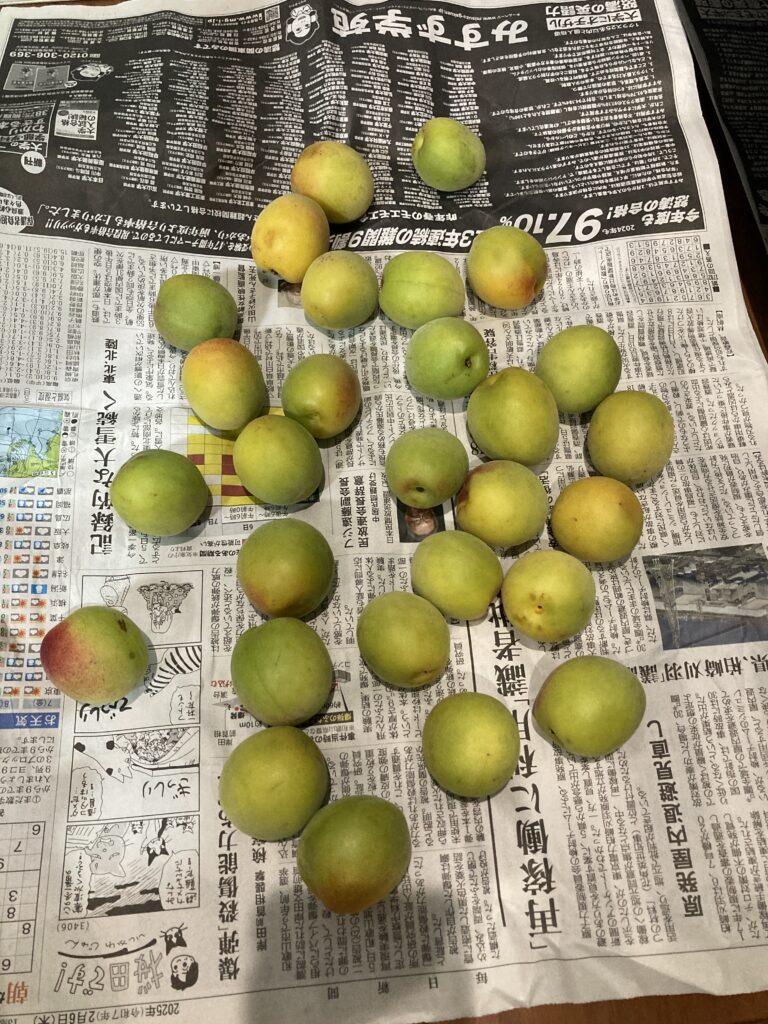

It started with a bag of ao-ume (green, unripe plums) from the store. They had that sharp, fresh fragrance that makes your mouth tingle just by smelling them. Since they were still quite hard, I let them ripen at room temperature for a few days. Slowly, their green hue softened to a golden yellow and the aroma deepened—almost like apricots with a floral note.

This year, supermarkets near me didn’t have ao-ume until June, and it said it’s a bit late. Wakayama prefecture is famous for ume production, but it said typhoon last year had severe effects. I went to couple other stores, and at last, I found some from Odawara (Kanagawa prefecture).

I wanted to buy fully ripe ume, but I couldn’t wait.

It’s important to let your ume out of the plastic bag as soon as possible. Ume continues to breath, and soon the plastic bag will be full of dew from condensation. Water may damage the fruit. Lay your ume inside, avoid direct sunlight.

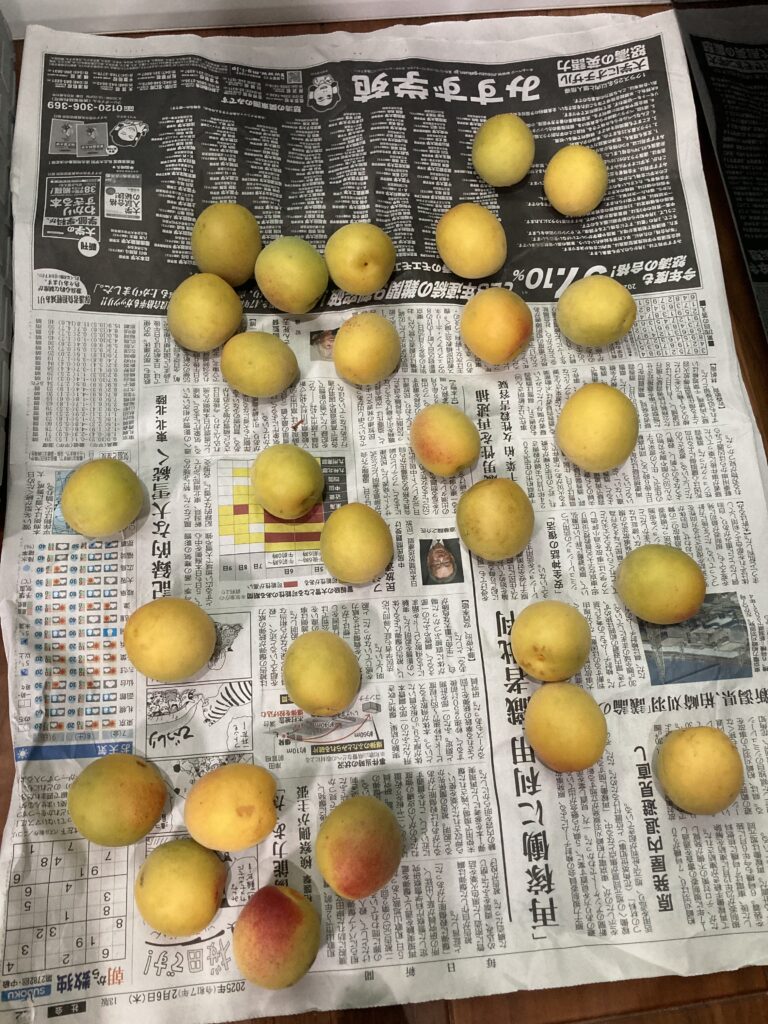

🔍 Step 2: Sorting Plums by Condition

When they were ready, I sorted the plums. Some were flawless—smooth-skinned, unbruised. Others had tiny blemishes or soft spots. Traditionally, the perfect plums are used for umeboshi, which undergo a long process of salting and drying. Plums with slight damage can still be incredibly useful—they’re perfect for syrup.

This way, nothing goes to waste!

🧂 Step 3: Preparing Umeboshi (Pickled Plums)

The unblemished plums were carefully washed and dried. Use a toothpick to remove stem from each ume. Don’t forget to dry the moisture in the hollow after removing the stem.

I’m still learning myself, and read that about 18~20% of salt is the standard. This time, I decided to go for 20% for extra safety. I hate to have mold on my very first umeboshi!

You can use glass jar or enameled container, but even more easily, use plastic zip bag! Measure your total ume weight. Mine was 595g.

20% of 595g is 119g. Add 119g of salt (okay, I have 120g). Extra safety!!

Now, I wait for umezu (plum vinegar, but it’s not actually vinegar) to rise, a natural brine that will preserve the fruit. I read it will be about 2~3 days. Later, these will be sun-dried and maybe turned red with shiso leaves. It’s a long process, but that’s part of the charm.

Umezu is starting to come up, but not yet complete. Do you notice the change in size?

And it’s starting to smell very very sweet! I’d advise to have a plate or container underneath the plastic bag in case it breaks.

🍯 Step 4: Making Umesyrup with Rock Sugar

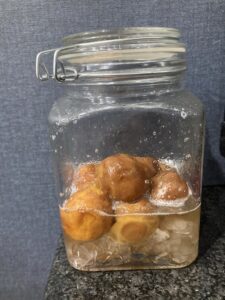

For the slightly bruised plums, I chose another method: umesyrup. I placed them in a jar alternating layers with rock sugar. Over the coming days, the sugar will draw out the juice and create a sweet, tangy syrup that’s perfect mixed with water or soda water in summer. It’s also a wonderful way to preserve the plums without alcohol.

You should shake at least once a day. But I love watching the slow melting process that I can’t count how many times I actually shook.

I noticed some bubbles. At first, I thought I gave my ume too much shake. I did my research and it was likely that it started a natural fermentation, which is not good for my current experiment. When I opened the lid, it smelled like alcohol. Yup, fermentation.

I decided to add some vinegar to kill the natural yeast on ume. I’ll keep my eyes on this sweet version too!

☔ A Quiet Joy in the Rainy Season

In Japan, the rainy season is called tsuyu (梅雨), literally “plum rain,” because it coincides with the plum harvest. There’s something deeply satisfying about aligning with the seasons in this way, doing the same tasks our grandmothers and great-grandmothers once did.

I’m still new to umeshigoto, and I’m learning as I go—but it has already become one of my favorite seasonal rituals. I can’t wait to taste the results… and next year, I’ll be even more prepared!